I started 2016 with a commitment to watch 200-something movies that I thought anyone who loved cinema should see. The goal was to fundamentally understand why films do what they do: why do they cut here, why do they cue music here, why do they move the camera here. It was a learning process as much as it was just a film addict inhaling his chosen form of drug. But the overarching goal was to see as many film classics as possible so I can finally create my Best Films Ever list–something that has percolated in my mind since the very concept of cinema became alive to me sometime in 2009. I started with a list that I had shared earlier here (Letterboxd List), but as the year went by and as the availability of these films varied, I had to make changes to my screening.

The Travelling Players lived up to my expectations and more. I love it.

Overall, I made some startling (at least to me) observations about my viewing habits and about how I generally think about these films. Firstly, I am susceptible to liking a film for the sake of not breaking consensus. Certain films have a legendary stature that one surely doesn’t want to dispel, if only because it makes you seem out of your mind to think that what many people who’ve been watching movies far longer than you have, and who are probably smarter than you, are well, just okay or worse of all, crap. This was most evident to me upon watching certain films this year: Terry Gilliam’s Brazil was very well-decorated, I thought, but its humor felt overly broad and kind of desperate to me; Tie Xi Qu, Wang Bing’s “monumental” 10-hour documentary, at first felt great because I thought it covered so much ground about…well I don’t know what about really. I gave it an A-rating though. But when I thought about it a few days or weeks later, I was kinda mad at the film. It was so indulgent in how it forced audiences to go through all that snow and smoke, when it could have done so in less time, and with–which I will now admit fully–little payoffs. I think I was probably congratulating myself on getting through 10 grueling hours of the mundane and dust so I gave it that rating to justify watching all of that. And lastly, and I think most painfully to admit, Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard, which many critics, including Roger Ebert cite as his masterpiece. What critics say is a rich examination of a prince’s stately reaction to a dying world, felt like a beautifully crafted and exquisitely rendered, but ultimately boring depiction of rich people being haughty and vainglorious. It was full of caricatures that felt utterly un-illuminating, and even offensive on some counts. I still think its craft is A-rating worthy, but for the little emotional investments one can make in what feels like a hollow picture, it’s definitely and most certainly not Visconti’s best.

Visconti’s The Leopard is so dull, I wished I liked it better. I tried hard to love it.

Visconti’s film is a great jumping point to the second observation I made about my viewing habits. I have such great expectations about certain films that at times, it blinds me to their flaws, or if its flaws are utterly unacceptable to me, I come down even harder on them. Because Senso was such an utter delight for me, any of Visconti’s films would have made for necessary viewing, especially when film critics I trust give such high ratings for them. The Leopard was one of ten movies last year that I was most dying to watch, so to see it flatline, I was thoroughly disappointed. Still, after viewing it, I had convinced myself that I just didn’t really understand what was happening or that it’s really really good, so I just overlooked certain elements. But no…a week later, when you’re done with your denial, you start to actually look at the facts, and the fact is, you just didn’t care for it. At all. Several movies this year did that for me. Most egregiously, Billy Wilder’s wildly overrated The Apartment. This pungent “romantic comedy” was one of the most misguided films I’ve ever seen onscreen, mostly because its very concept was gross. What Wilder found funny, that whole suicide moment for example, felt thoroughly insulting and maybe even ignorant.

Red Desert got me feeling like… I’m lost in mist.

And my last observation is that I tend to have certain biases for and against certain stories. I have an absolute distaste for films that often center on the ennui that rich people feel. It feels so utterly meaningless to me. As such, Michaelangelo Antonioni’s films are definitely not my type, unless they’re doing something else that feels new or exciting. The biggest victim this year is his film Red Desert, where characters just drift around and try to feel things in the middle of an industrial complex. The Leopard fits into this problem I have with “first world problem movies” as well. Preachy philosophical or socialist films are also not my type–Jean Luc Godard’s Weekend feel incredibly brazen and a touch insane in the first half but settles for his usual endless preaching of socialist-leftist-whateverist doctrine that sinks the second half and the entire film for me. It’s not that I don’t understand or even empathize with his thoughts, I just prefer seeing it incorporated in images and action, rather than pure dialogue. Lastly, Buddhist movies tend to put me to sleep, mostly because they rely on the whole idea of Zen, which may seem spiritual to others, but to me is just too meditative to really stay awake. As such, I struggled to get through Kon Ichikawa’s The Burmese Harp mostly because it was too “peaceful”, for lack of a better word.

On the opposite end of that spectrum, I have a special place for Catholic films, owing in part to my upbringing. Therefore, it wasn’t a surprise that Robert Bresson’s The Diary of a Country Priest became one of my favorite watches this year. In addition to being so technically excellent, it was also just an astonishing affirmation of Catholic faith. Similarly, I’m a sucker for huge historically sweeping stories or epic canvasses of life through a historical lens. Theo Angeloupolos’s The Travelling Players was my favorite of its kind this year.

In any case, in lieu of talking about all the films I’ve seen, I’ll give a rundown of several that I found noteworthy for one reason or another:

The best movie I saw for the first time this year: Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest is an exceptionally told film on faith and spirituality, and does it through such simple techniques (fading background to black, shooting the priest behind bars, etc) but so precisely and so economically, that it reveals so much depth within the material. Claude Leydu as the priest gives probably one of the five performances I’ve seen onscreen.

Leydu is so amazing, one shudders to think of living up to a performance like that.

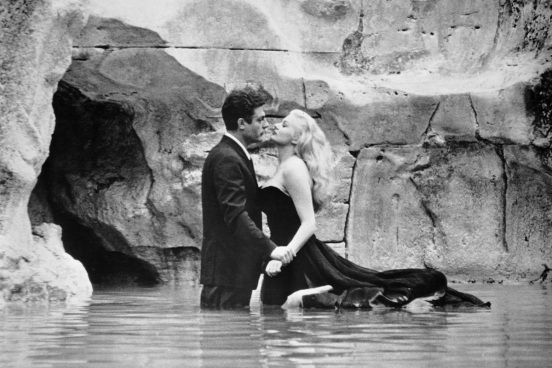

Runner up: Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita feels quite unusual for me in that while it portrays topics that I normally shun as I’ve noted earlier, they feel extremely well-drawn and well-examined. The beauty of Fellini’s film is that the landscape he creates here feel less gawdy or excessive than his earlier efforts, and they also feel spiritual in ways that his other films don’t.

Gorgeous. Utterly gorgeous.

The worst movie: Eddie Romero’s Ganito Kami Noon, Paano Kami Ngayon (As We Were) has to be, hopefully, the most lauded Filipino film that also egregiously suffers from its own pretensions of grandeur. Despite its picaresque images, and well crafted sets and costumes, everything from sound design to its ghoulish acting, to the damn score is so fraying and poorly judged. The editing is perplexing and wishywashy, and the plot is so ludicrous with characters that function more like set pieces and caricatures than real humans. There are bits that are good, especially the funny stuff at the beginning, but I don’t understand its status in the Philippines.

The father-son duo from You Were Weight But Found Wanting absolutely sucks here.

Runner up: Mikio Naruse’s Floating Clouds is, sad to say, the wrong kind of melodrama for me. Melodrama tends to have a negative connotation but not in my world. When done correctly, they feel closer to real life feelings filtered through sound, performance, and visuals. Imitation of Life or Secret Sunshine are two examples of excellent melodramas. Naruse’s Floating Clouds, on the other hand, feels painfully forced. The music often dictates what you should feel ahead of the “moments”, the visuals don’t say enough, and the performances oscillate between too self-conscious and too unsubtle. Worst of all, the situations themselves feel awfully mopey: no balance between good and bad situation, just completely a descent into suffering.

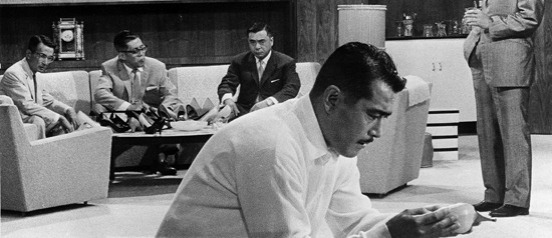

Biggest Surprise: I did not see Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low coming. Kurosawa is most well-known for his epic historical flicks, chief among them Seven Samurai, Rashomon, and Ran. But forget about those films, because if you want the lowdown, Kurosawa’s absolutely finest hour is not any of those worshipped movies, but it’s this tightly coiled thriller that has few equals in world cinema. Having seen many of his previous works, I was sure I had an idea of what kind of director Kurosawa was–the showy kind, who draws attention to the craft, prefers spectacle over quiet dramas. But this is nothing like that. This is so subtly crafty, suggesting so much about what’s going on through the use of images, and how he carefully rearranges them. He navigated the push and pull of the drama so expertly, that by the end of it, my heart was racing. Few films can give me that kind of rollercoaster thrill, and even fewer have done it with such technical mastery. Bravo.

High and Low, Kurosawa’s true masterpiece.

Runner Up: Viewing Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion comes with certain expectations about the master director. His film Rules of the Game is in the top 10 films of all time, and even though I thought it was very intelligent, it’s not exactly the most entertaining time at the cinema. It felt so stuffy and hit you with too much class discussions that I felt removed from the whole viewing experience. Thank goodness for Grand Illusion. This film has the same level of intelligence, but its humor is so much more accessible. Its criticism of class feels more organic to the piece, as it should since the film takes place in the middle of a world war. Not to mention its unimpeachable graceful camera movements. Few viewing experiences this year felt as joyful, as fun, and also as cerebral as this one.

Renoir’s The Grand Illusion was such a grand experience. See it.

Biggest Disappointment: Obviously, The Leopard. See above.

Runner Up: Jacques Tati’s Playtime. I so wanted to like this given its very nature, but I think I got tired of the visual tableau motif around the 30-minute mark. I honestly don’t think I was born with a Tati funny bone. Like Roy Andersson after him, Tati’a tableaus are incredibly detailed constructions, lensed so well to capture such awesome still frames. The choreography is the obvious highlight as the film basically changes subjects as new characters enter the frame. There are certainly amusing moments and I did chuckle a few times, but mostly I was amused when I was expecting some side splitting comedy. Not for me though I admire its technical proficiency.

Film I Probably Won’t See Again: Klimov’s Come and See joins the ranks of Grave of the Fireflies and Shoah of films that, as extraordinary as they are, can never be viewed again because they impose such pain on my spirit and my mind, that viewing them again will possibly be torturous. Klimov’s film is all about perspective and his focus on what the child sees and feels and hears, gets you in the mindset of that kid. Therefore, you feel the same things he feel when he experiences these moments. But that kind of closeness to the character is paralyzing and I’ve had anxiety thinking about these images, so I’d rather not do it again. Great film though.

Traumatizing.

Runner Up: Kim Ki-young’s Woman of Fire is probably one of the worst remakes ever, and from the same director who made the original. True, there’s value to watching Kim’s use of colors and a more opened-up set-up to capture the changing times of Korea more accurately, but whereas the original The Handmaiden dwells on the excellent psychology of its star performance, this film decides to make her feral, animal-like, and so utterly and comically inhumane, that it left a sour taste in my mouth. Utterly repugnant.